What is Your Housing Journey?

Close your eyes…

Transport yourself back to the first home you lived in when you were a small child…

Imagine walking through that home. Which areas hold your fondest memories? Who lived with you? Do you remember your neighbors? Were there other kids living close by? What was your neighborhood like?

Now open your eyes…

If you’re at home as you read this, look around, what do you see? Who do you see? Look out one of your windows, what surrounds your home? From the time you were born to the present, how varied have your housing experiences been? How did you get from there to here?

Linda's Housing Story: From There to Here

Hong Kong, China

Vancouver, Canada: Then

Vancouver, Canada: Now

Why do our housing stories matter?

Why is it important to jog our memories of the various places and spaces we’ve called home? Because each of the homes we’ve lived in has been a step in our individual housing journey and brings unique perspectives to how we process the complicated issues surrounding housing in the communities we live in. Every time we see the headlines about soaring housing prices, increasing mortgage rates, a new construction project in our area, a growing homeless population, and the uncertain future of housing, we can better appreciate the complexity faced by the community, and the need for a multitude of solutions that can effectively work together to tackle the housing crunch.

Data Driven Stories

America’s Housing Journey: From There to Here

Up until the turn of the 21st century, the financial variables of homeownership were well-defined and concrete:

- Determine how much you can afford with the principle of home financing that mostly translates into the monthly mortgage payments or rent shouldn’t be more than 30% of your gross monthly wages.

- For homeownership, plan to save at least 20% of the home’s purchase price for a down payment along with other purchasing and closing fees

- Anticipate paying off your home in about 30 years at a monthly interest rate that ranges from 8% to 12% (pre-2000s)

Use the equity in the home to move up the property ladder (e.g. from a condo to a townhouse to a detached house)

Over the past 20 years, these tried-and-true basics of homeownership have been challenged because of several interrelated shifts:

- Increase in housing prices has outpaced the rise in income, making housing unaffordability a compounding issue for the last three-and-a-half decades. From the mid-1980s to 2021, the median incomes in the U.S. rose about three-fold (from $22,415 to $70,784) while median housing prices for the same time frame increased five-fold (from $78,200 to $423,600).

Housing rental prices have seen their own increases, with almost half of Americans (46%) spending more than 30% of their gross income on rent and about a quarter of Americans (23%) spending 50% or more on rent.1 - With house prices and rents either consuming more income or becoming more out of reach, the pressure is on to increase access to different housing options—namely affordable housing options. Yet, there is a chronic shortage of affordable housing in most U.S. cities. [Read more about the lack of affordable housing in various American cities.]

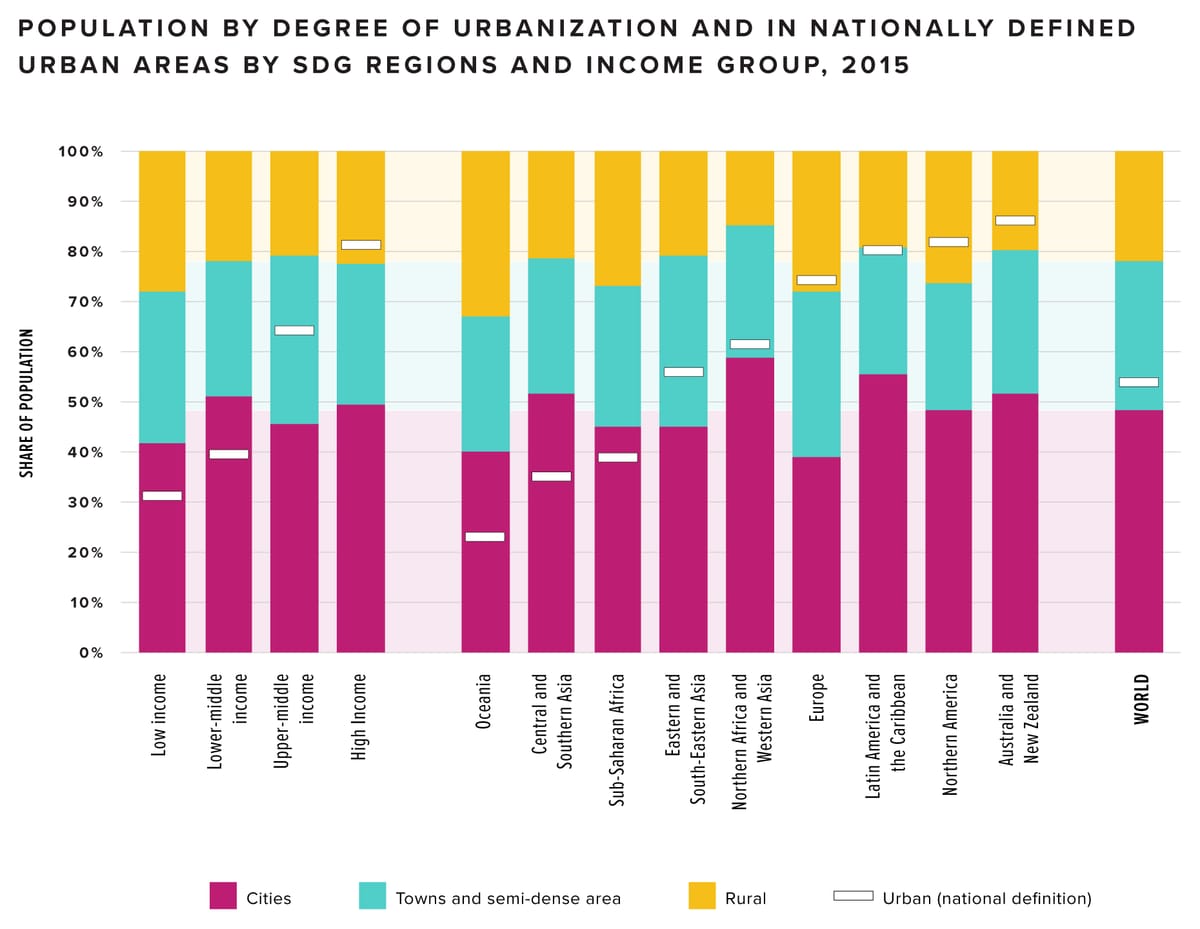

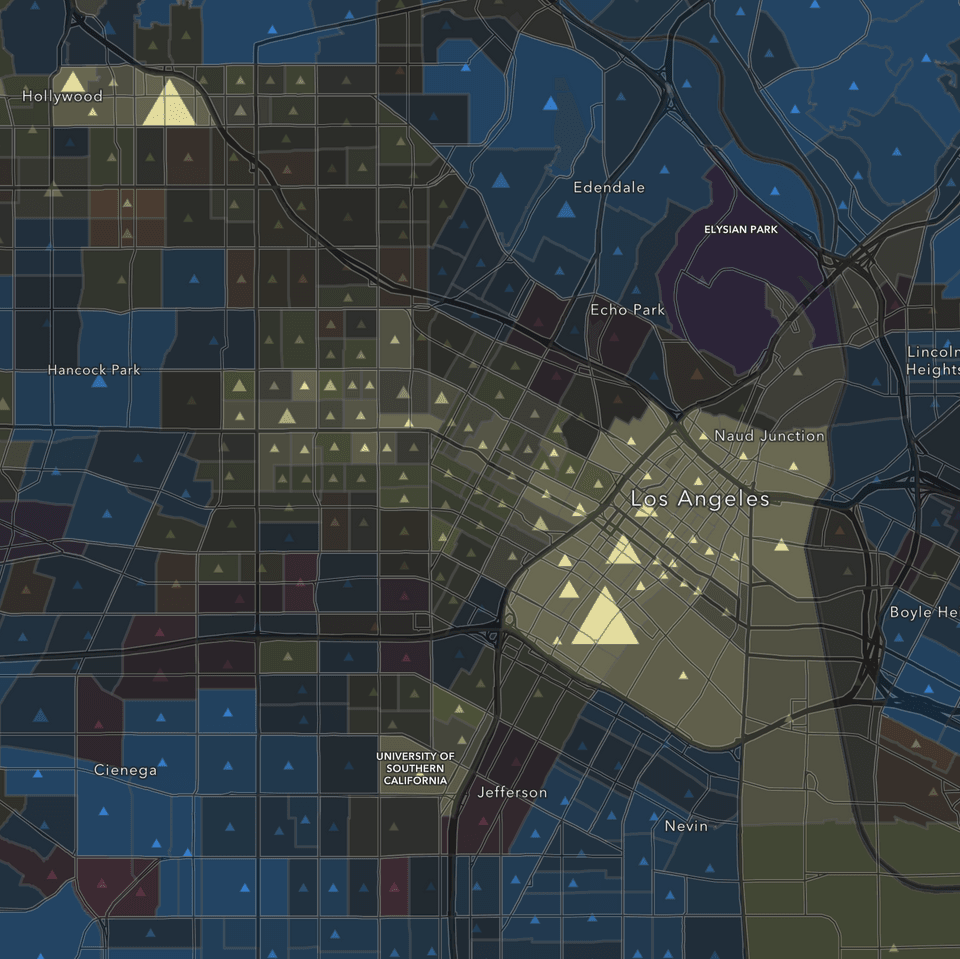

- The concentration of high housing prices and the lack of supply is focused primarily on urban areas. Currently, 80% of the U.S. population lives in urban areas. Characteristic of urban areas, there is the lack of vacancy (under 1%) in both houses for sale and rent purchases, leaving people with little choice. [Refer to a visual summary of American urbanization since the 1700s].

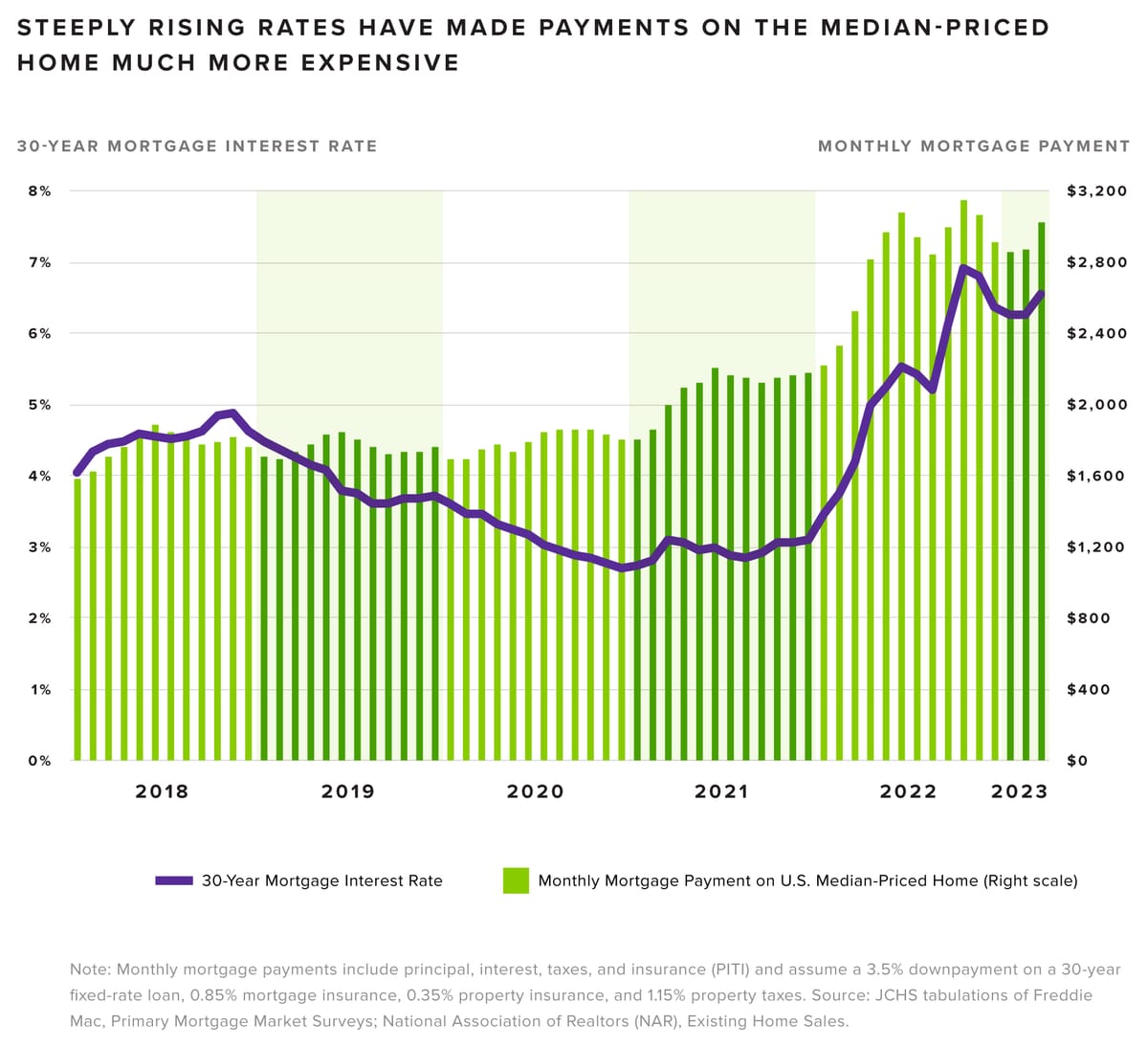

- The recent and magnifying effect of the back-to-back Federal Reserve interest rate hikes (between March 2022 to July 2023, 11 interest rate increases occurred) to address inflation has increased borrowing costs. The national average rate on a 30-year mortgage is 7.5% (as of October 2023), a 20-year high2—making homeownership, particularly amongst first time homebuyers, less appealing and affordable.

- More extreme weather across the United States has led to more displaced residents with three million Americans evacuating their homes in 2022 alone (compared to a yearly average of 800,000 displaced individuals from 2008 to 2021). [Read more about the impact of natural disasters and displaced Americans.]

Housing Well-being

At the confluence of these five forces is the crux of the housing problem in the U.S. and its impact on housing well-being.

Housing well-being encompasses three critical components:

- The ease and ability of individuals to buy and sell their homes, with the home being a wealth-generating asset;

- Quality assurance of the physical home to ensure a safe (structural) dwelling to shelter from external threats to one’s physical health while fostering a healthy home environment; and

- The vibrancy of a community to offer various housing options addresses a variety of other needs. Where people live should have: access to good education, assurance of essential services for all residents, and positive economic growth (such as thriving small businesses).

The Housing Continuum

Because of the complex changes facing housing in the United States today, it is beneficial to view the housing market in a broader, more systematic fashion to include the different forms of shelter needed to house residents at any point in time.

The Housing Continuum aims to ensure sufficient housing for all people in the community and recognizes the demand and supply of each type of housing will impact the overall flow of housing across the continuum. While the Housing Continuum may be interpreted in a linear fashion, cities and community organizations that have adopted this model appreciate that movement along the continuum is often not linear.

While each type of housing along this continuum describes a discrete housing type, it is not hard to imagine the constant movement of people along this continuum. Circumstances may result in some people moving left to right on the continuum and other individuals moving right to left.

For credit unions and community partners providing various housing solutions along this housing continuum, consider interventions and actions within a system in order to avoid unintended consequences that exasperate housing problems in other areas along the continuum.

Credit Unions in the Housing Continuum

Credit unions have demonstrated their support in addressing the housing concerns in the communities they serve. Understanding the challenges faced by members at the local level as well as identifying local organizations at the forefront of addressing the chronic housing needs of residents along the housing continuum represent two key factors to effective, long-term involvement in improving the housing situation.

In addition, there are a variety of ways for credit unions to provide funding to improve housing conditions in the community they serve. Credit unions may tap into federal loans aimed at low-income housing development, invest in the affordable housing landscape through a foundation arm, or offer products to members that have an added goal to address affordable housing.

Here, we highlight the experiences of how some credit unions supported their local communities’ housing concerns.

While these examples showcase how credit unions have proactively tackled the housing needs in their communities, what are considerations for credit unions in general when determining how to address housing needs of members and the housing issues at large?

Grappling with Housing Issues: Considerations and Implications for Credit Unions

Rethink the Mortgage Business

In the United States, homeownership sits at 66%.3 However, almost three-fourths of these homeowners (75%) are not mortgage-free and continue to service their debts.4 This roughly translates into residential mortgage debt totaling $11.92 trillion as of the end of 2022.

Various players—the banks, mortgage companies, and mortgage brokers—provide mortgages, crowding out credit unions from serving their own members for home loan needs. Across all credit unions, on average, they provide about 2.4% of their members’ first mortgage loans. As a comparison, credit card penetration at credit unions is an average of 18%.5 Credit unions are at a disadvantage because the mortgage business is often a scale business, with many credit unions not having enough deposits to fund the home loans for their members.

Meanwhile, to make things even more complicated, alternative financing options to the traditional residential mortgage are entering steadily into the marketplace. About 1 in 5 homeowners have borrowed through alternative means at least once in their lives.6 While some of the alternative financing products are designed to address the housing needs of low-income families, multigenerational households, or multiple homeowners (i.e. those not from the same families) in a fair and transparent fashion, some alternative products have been flagged as risky, such as some lease-to-purchase products that require a “buyer beware” warning.

And, as mentioned earlier, the once predictable variables of homeownership are no longer valid. Accelerated housing prices make it harder for a prospective homebuyer to save for a down payment and the debt-to-income burden of the mortgage makes homeownership unaffordable for more and more people.

For credit unions, it’s time to rethink the mortgage business:

- In addition to considering ways to increase mortgage originations, identify the areas or niches (type of housing or homeownership) that would best address the housing crisis faced by the credit union membership—and by extension the community. Investigate the necessity and viability of government-backed loans such as HUD (United States Department of Housing and Urban Development) or FHA (Federal Housing Administration) loans to fill in the gaps of the community’s housing needs.

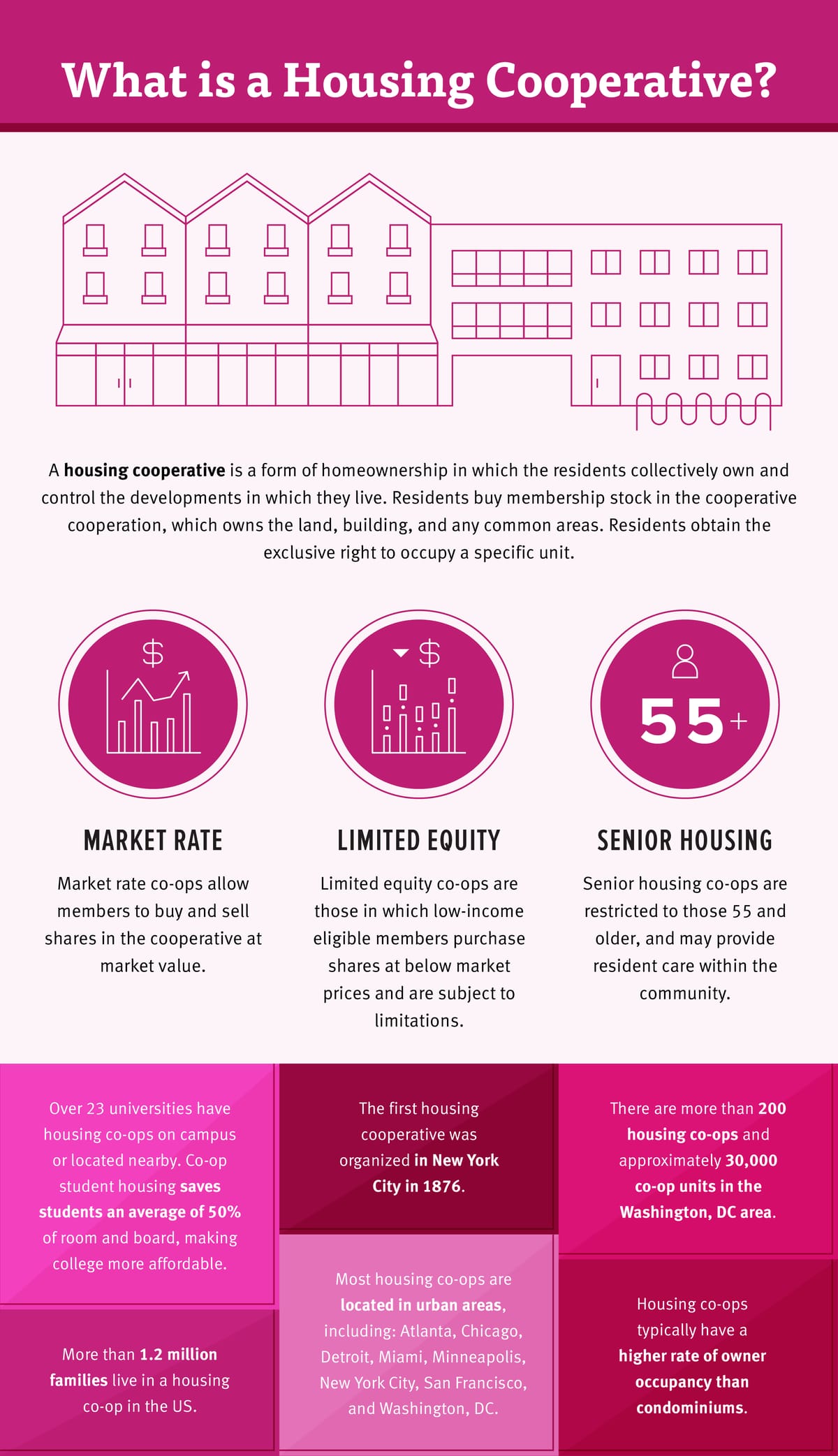

- Look at ways to be become a big player in the alternative financing space with a special focus on the cooperative models. This includes looking at providing members access to co-operative housing or financing co-op housing construction.

- Reimagine what homeownership means when it comes to member financial well-being. Rather than only looking at ways for members to traditionally own a home (via a residential mortgage), work with members to evaluate their current housing well-being and how they wish to improve it. For instance, invest in making members’ current home safer, more adaptable to changing climate patterns, or extend their current home’s footprint.

Articulate the Strategic Overlay: Housing and Social Impact

Housing challenges have become a more prominent social issue as each decade passes. As mission-driven organizations, credit unions must determine how tackling the housing issues in their communities fits into their current social impact priorities.

Looking at housing through a social impact lens is a separate, yet complementary, endeavor to providing home loans for members. However, the strategic prioritization of housing requires discrete steps and discipline to carry out the investigation and ultimately the commitment of time and resources to realize set social impact goals.

The starting point for each credit union will begin differently:

- If your credit union doesn’t have a social impact strategy, the first step is to explore what that means and entails. Read Filene’s report on a Guide to Creating a Social Impact as a starting point.

- If your credit union has an existing social impact strategy, refer to the key areas of priority and determine whether addressing the housing crisis is aligned with those priorities directly or indirectly. For instance, say affordable housing is not one of your credit union’s key pillars, but addressing climate change is. How housing fits into that may be to support community organizations that are constructing new developments to future-proof extreme weather changes. Or, it may be to prioritize more member loans towards energy efficient heating and cooling home solutions. This is the hard part of strategy—making trade-offs and being clear about what efforts to focus on rather than focusing on everything related to housing.

Closing Remarks

The Power of Stories: Housing Experiences of Members and the Community

While the facts, reports, and resources shared in this brief allow the reader to better understand the housing issue, it is the individual stories of our housing journeys that we will most remember and inspire us to make a positive change.

It is imperative for credit unions to hear the housing stories of its members and residents in the communities they serve. Just as we started with sharing our own “from there to here” housing journeys, create opportunities for individuals, families, and underrepresented groups in the community to share their own housing journeys. These stories will help guide credit union strategies in the areas of: member housing well-being, community outreach, and social impact.

Stories can be heard and collected in formal or informal ways—the key to sharing them centers around building collective understanding.

- Begin simply with asking friends or colleagues what their “from there to here” housing journeys are.

- Leverage existing member research programs (i.e. surveys, focus groups) to explore housing experiences and unique housing journeys.

- Venture into the communities to listen to stories that represent the entire housing continuum.

Use these stories to inspire and direct positive change and housing solutions for the community. For a topic as vast and complicated as housing in America, this brief but scratches the crux of the nuanced challenges and vast solutions at hand. Rather, the information presented is intended to propel the reader to bring a more urgent voice to the housing crisis and arm the reader with talking points and tangible solutions from other credit unions that have positively impacted their communities.

Endnotes

- Pew Research: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/03/23/key-facts-about-housing-affordability-in-the-u-s/

- Freddie Mac: https://www.freddiemac.com/pmms

- Census Bureau, Q3 2023: www.census.gov

- OECD, Housing Taxation in OECD Countries, 2022: https://www.oecd.org/publications/housing-taxation-in-oecd-countries-03dfe007-en.htm

- Callahan and Associates PEER Tool (powered by NCUA call reports): https://www.callahan.com/

- Pew Trust: https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2022/05/millionsofamericanshaveusedriskyfinancing_brief.pdf

Resources

Stories, Studies, and Interactive Tools to Explores Key Housing Issues

Deeper Dive into Housing

This brief provides an introduction into the main housing issues faced today. The following reports are suggested to deepen your knowledge on this complex topic.

- For a comprehensive investigation into the housing market in the U.S., read the State of Housing Report 2023 by the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University

- The global perspective on housing is explored in Habitat for Humanity’s Envisaging the Future of Cities

Extended Readings

No less important is the history and economics of housing. Due to the limitations of this brief, topics such as the impact of housing policies, broader macro-economic policies, financialization of housing/real estate, and the collinearity of poverty and race in accessing housing were not included. Books written that examine these important topics in vivid detail include:

- “Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing Systems” by Jenny Schuetz

- “Race for Profit” by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

- “Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing” by Josh Ryan-Collins, Toby Lloyd, and Laurie Macfarlane

- “The Color of Law” by Richard Rothstein

FILENE’S CENTER FOR COMMUNITY SOCIAL IMPACT IS GENEROUSLY SPONSORED BY: