Executive Summary

In 2015, Filene Research Institute launched the Reaching Minority Households (RMH) Incubator to identify programs that could help financial institutions like credit unions and community banks more effectively reach and support financially vulnerable households and communities of color. With the support of Visa and the Ford Foundation and in partnership with dozens of credit unions, Filene tested the relative demand, consumer impact, scalability, and financial sustainability of five different lending products designed to improve financial access for these populations. Among the products tested were alternatives to payday loans, small-business microloans, and a non-citizen ITIN (Individual Taxpayer Identification Number) lending program. In total, 40 credit unions issued 58,482 loans totaling $84.8 million (M), impacting 18,559 consumers.

What is this research about?

In this report, we describe new research that builds on the RMH Incubator by tracking the longer-term outcomes of three programs—ITIN lending, Payday Payoff installment loans, and QCash™ small-dollar loans—through the lives of 20 people who participated in one of these programs at one of four credit unions: Freedom First Credit Union in Virginia, Illiana Financial Credit Union in Illinois, Point West Credit Union in Oregon, and Washington State Employees Credit Union (WSECU) in Washington. We describe outcomes specific to each program, as well as cross-program findings across two time horizons: 0–6 months after receiving the loan (which we group together as short-term outcomes) and 6–18 months after receiving the loan (medium-term outcomes).

We also detail the benefits of access to financial services and provide a rich qualitative dataset that shows the complexity of conditions structuring financial inclusion. We emphasize how access must be accompanied by other interventions over time to lead to financial well-being. In allowing loan recipients to reduce their financial vulnerability in the short term, RMH program participation also resulted in a broadening of perspective or opportunity that led to longer-term impacts. These include the following outcomes:

- Reduction in immediate financial vulnerability alongside the development of a clear pathway to future financial well-being.

- Engagement by participants across multiple touchpoints with institutions and programs during the programs and beyond.

- Changes in participants’ material prospects in the financial system (external changes) that were accompanied by changes to participants’ beliefs and behaviors (internal changes).

- Goal setting, planning, and reflection by participants as part of their experience in the programs.

We conclude the report with a strategic discussion about issues that financial institutions face when trying to build such pathways to sustained consumer and community impact.

What are the credit union implications?

Financial institutions must understand that long-term consumer impact requires converting short-term gains into strategies and supports for individuals to imagine or envision longer-term growth and success, plan for larger financial goals, take action, and see improvements in their future financial well-being. Inclusion—basic access to financial services—can result in immediate need reduction. But to take root, access must also be paired with a more substantive sense of security, capability, and resilience.

Ultimately, access to credit is a necessary but not sufficient condition for improved financial well-being.

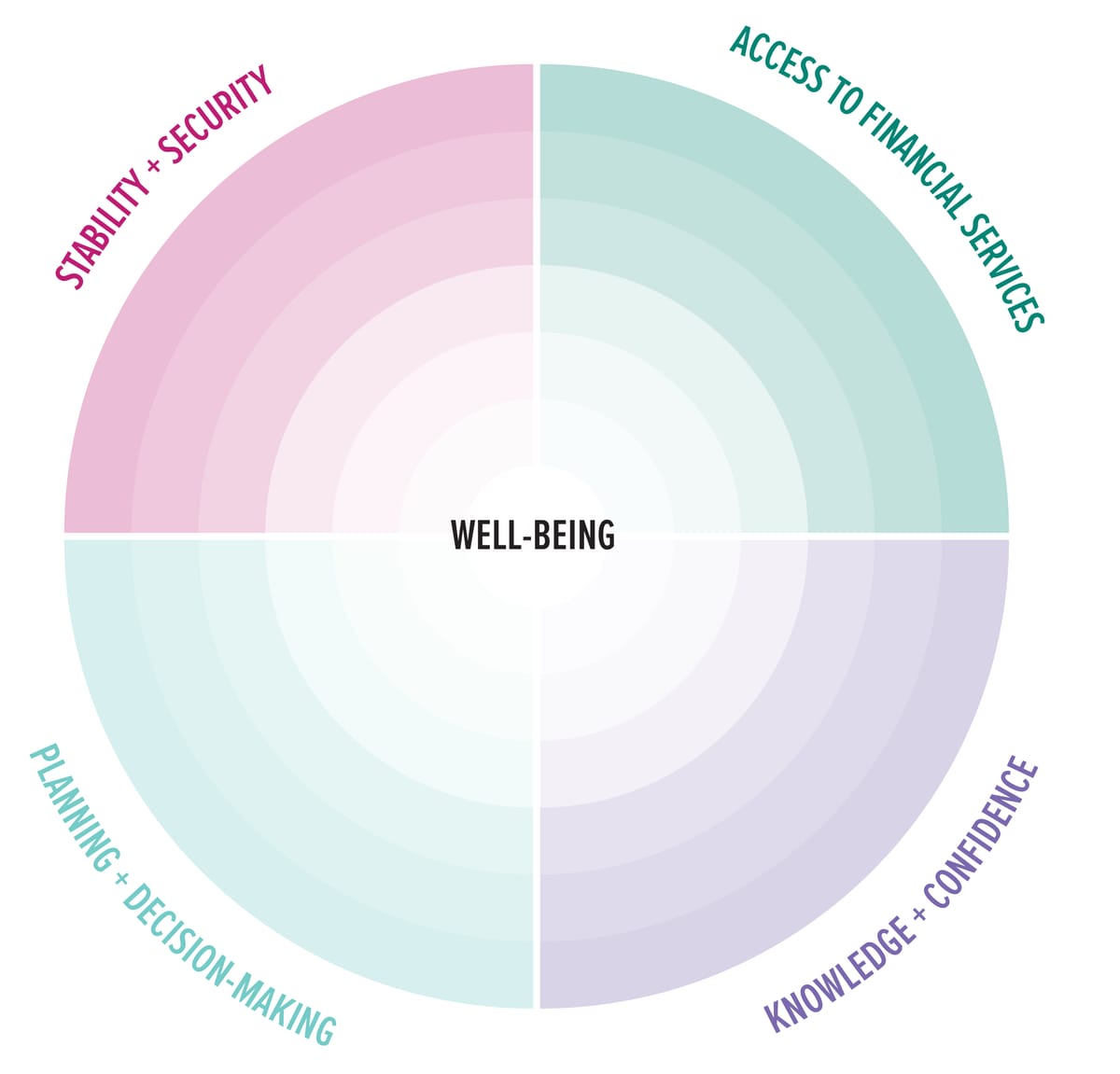

Financial inclusion unfolds over time and in fits and starts; similarly, financial well-being is not an all-or-nothing proposition. Accordingly, financial institutions must begin to support consumers in a sustained manner along multiple dimensions of financial vulnerability. To aid financial institutions in designing products and support services with the goal of creating long-term, positive change for consumers in need, we introduce a Pathways to Financial Well-being model. This model encourages financial institutions to incorporate the complex dimensions of financial vulnerability and well-being in their routine engagement with consumers.

Dimensions of the Pathways to Financial Well-being Model:

- Stability and Security: capacity to absorb shock and adapt to changing circumstances.

- Access to Financial Services: capacity to access and use high-quality, low-cost financial services, including credit.

- Knowledge and Confidence: capacity to navigate financial services and control one’s finances.

- Planning and Decision-Making: capacity to make complex decisions and plan for the future.

To operationalize this model, we urge financial institutions to take on new roles and reimagine themselves as a service provider, a coach, and an advocate.

Through the stories of a small group of consumers, this report provides a practical guide and inspiration for those striving to improve their community’s financial well-being. Will you be one of these leaders?

Filene thanks Visa for making this research possible.