Open banking is all about the financial services data supply chain—and thus all about stuff like … Can we finally get rid of screen scraping? What kinds of Reg E, Reg Z, and other accounts “count” when it comes to third-party data sharing? What makes for a good independent standards setting organization? How does API uptime and transaction response rate impact user experience? In other words, it can get a bit technical.

But credit unions should be preparing for how open banking may transform the competitive landscape of financial services and accelerate changes in how consumers relate to the already-fragmented financial services provider landscape. Especially because this fall, the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) is expected to release a final version of a rule proposed almost one year ago that would “accelerate the shift to open banking” (in the words of CFPB Director Rohit Chopra himself) by outlining a plan for industry implementation of “Section 1033” of the Consumer Financial Protection Act (aka Dodd-Frank), which guarantees consumers the right to access and share their financial data.

What’s at stake? An even more competitive financial services marketplace. New technology and compliance requirements for financial institutions, fintechs, and the data intermediaries that connect them. And the real possibility of shifts in how credit union members relate to their credit unions.

What are the open questions about open banking? What are we looking out for in the CFPB’s forthcoming open banking rule when it comes to implications for credit unions? As always, thanks for reading! Let’s dig in.

What is open banking, and what is open banking supposed to accomplish?

Banking is, fundamentally, a data-driven enterprise. That’s a very 21st-century way of putting it, but even the oldest, most traditional and seemingly tedious parts of banking—keeping the ledger, assessing the creditworthiness of a borrower—are all about managing and interpreting information about people.

The core idea behind open banking is that this information, all the data that consumers generate through their interactions with financial services providers, is rightfully owned by those consumers. As a result, individual consumers themselves should determine who has access to that data, how that data is shared, and how that data is used. The CFPB’s proposed personal financial data rights rule provides a framework to implement consumer control over data, such that a broad subset of financial data could only be accessed and used by financial services providers with explicit consumer authorization.

The intention, then, is to empower consumers to have more control over their data—and thus over which financial services providers they use and what they use those providers for.

The core idea behind open banking is that all the data that consumers generate through their interactions with financial services providers is rightfully owned by those consumers. The intention is to empower consumers to have more control over their data—and thus over which financial services providers they use and what they use those providers for.

How would this work in practice? Consumers already rely on a variety of providers (banks, credit unions, non-bank fintechs) for financial services. Many of these services—payments, personal financial management, credit scoring and loan origination—require data sharing. Some of this happens through the perilous process of screen scraping, and many banks and credit unions have already formalized relationships with specific third-party providers to offer new or expanded services to consumers, often with an eye on improving experience and driving growth for the bank or credit union.

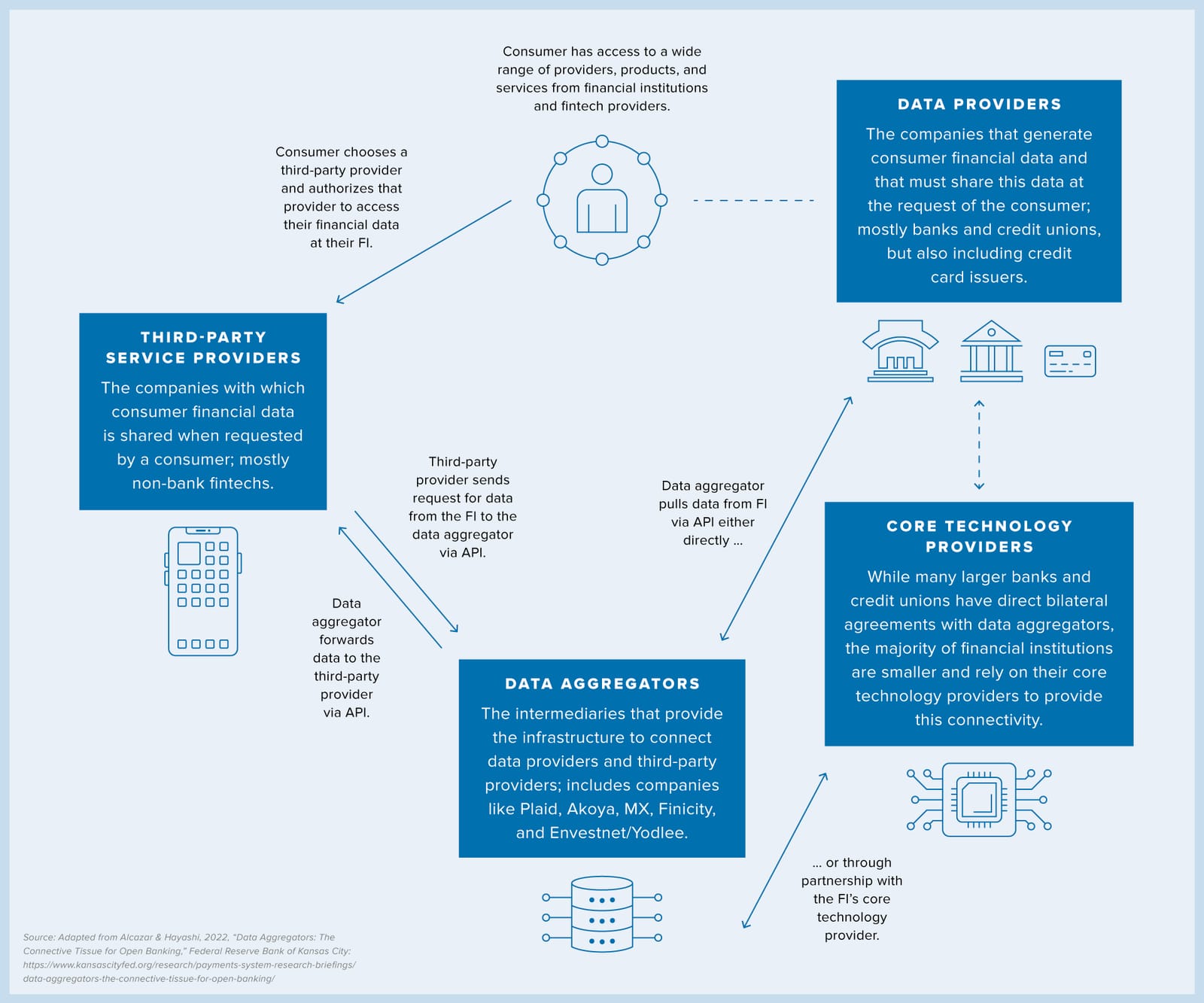

Open banking would allow consumers to choose which providers get access to their financial data by requiring financial institutions to provide access to that data to third-party providers through application program interfaces (APIs) and under a common set of rules and technical standards. The implementation timeline for credit unions for the CFPB’s proposed rule would vary between two-and-a-half and four years, depending on the asset size of the institution.

From the perspective of open banking’s champions—and the CFPB’s as well, based on the language of the agency’s proposed rule and Director Chopra’s commentary around it—open banking will have a number of benefits for consumers:

- Greater transparency and control by consumers around how their data gets shared

- Enhanced data privacy protections for consumers

- Increased consumer choice (and greater simplicity in switching providers) and thus healthier competition in financial services

- Continued fintech innovation

What does open banking mean for credit unions?

The truth is that open banking is already happening—but in limited and inefficient ways. Open banking rules will standardize the way data-sharing happens between financial institutions, data aggregators, and third-party service providers. Today, such data-sharing happens in two ways.

First, a significant amount of data-sharing happens through screen scraping, the risky and inefficient process through which a third-party extracts information displayed visually on a website like a bank’s or credit union’s online banking portal. Just about everyone agrees that eliminating screen scraping will benefit all parties.

The second way data-sharing happens is through bilateral agreements between data aggregators or third-party providers and financial institutions. While there are many banks and credit unions seeking to be proactive, in negotiating these deals one-on-one, the largest financial institutions have more resources and more leverage. What’s more, some players have become more aggressive at limiting or dictating the terms of third-party providers’ access to consumer data by requiring those companies to work with their chosen intermediary. Less well-resourced community banks and credit unions will be left to pick and choose which companies to work with, constrained by cost and capacity.

The standardization provided by open banking may level the playing field, allowing many credit unions to accelerate their partnership capabilities.

Nonetheless, conforming to new open banking standards will have a cost, and that cost will in all likelihood be mostly borne by financial institutions. (The proposed rule prohibits data providers from charging consumers or third-party providers to access data, although some have suggested revenue-sharing from third parties to financial institutions might be appropriate not only as a cost offset but to incentivize buy-in.)

While some credit unions are ahead of the game, for most, this will require necessary upgrades to legacy technology systems to provide data access through API integrations. Many will be challenged by infrastructure and talent capabilities, and most will be dependent on core technology providers and other partners to make these investments.

The cost and timeline concerns are real, especially Given many credit unions’ reliance on a robust provider ecosystem; implementation queues could lengthen as compliance deadlines near. The CFPB gives a timeline of between two-and-a-half to four years for credit unions to comply with the proposed open banking rule. But no matter what the final compliance schedule looks like, the reality is that a faster timeline for some financial institutions will create competitive pressure for all financial institutions, including credit unions, to adapt more quickly.

What are the opportunities that open banking offers for credit unions?

One could argue that paying the up-front costs of integration may be beneficial for all financial institutions in the long run, no matter the size or sophistication, as the consumer experience associated open banking becomes more expected and table-stakes. What’s more, most credit union leaders we speak to are generally supportive of more open infrastructures and more flexible partnerships; open banking rules might provide the impetus to get credit unions and technology providers aligned.

So how might credit unions seeking to be proactive go on the offensive? Open banking is not necessarily a one-way street, and credit unions can leverage the emerging open banking ecosystem for both competitive advantage and enhanced member insights.

First, credit unions will be able to use open banking partnerships with third-party providers to offer new products and services to attract new members while retaining and more deeply engaging current members. One big worry about open banking is that it will accelerate competition in an already extremely competitive industry. And it is true that open banking may make entry to the financial services market easier for new companies; indeed, this is part of the goal, to foster innovation. But the fintech ecosystem in the credit union industry is evolving rapidly away from competition and towards collaboration as many fintechs realize they will grow faster by enabling credit unions than by going head-to-head.

Credit unions are already leveraging such partnerships to provide payments, advanced personal financial management tools, investing and wealth management, insurance, financial health and education, and more. What more is possible? Might we see more streamlined onboarding? Better real-time fraud detection? Faster and more accurate automated loan decisioning? Point-of-sale lending and embedded finance? This is where open banking can get exciting for credit union leaders willing to get creative.

Second, open banking can provide credit unions with a more comprehensive view of members' financial lives. Today, few if any credit unions have a truly complete picture of their members’ finances, because the majority of consumers use multiple institutions for different financial activities and are thus not consolidating all of their money management at one institution. The account aggregation capabilities enabled by open banking could be turned to a credit union’s advantage by giving them information and insight they can use to fuel strategy and identify growth opportunities, tailor products and service delivery, and deploy in more advanced personalization, product bundling, and marketing. There are some limits here (see below), but as credit unions develop mutually beneficial partnerships with third-party providers, these kinds of opportunities open up.

In short, while open banking very well may intensify some of the challenges credit unions face in a competitive financial services marketplace, it may also give credit unions new tools to navigate those challenges! At the same time, if the goal of open banking is consumer empowerment, a healthy competitive market, and innovation in banking, then it is logical to offer a clear onramp for all institutions to reap the benefits and minimize the risks.

What are the open questions credit union leaders should be asking about open banking?

After reading this far, you might be anxiously preparing a risk mitigation matrix or enthusiastically brainstorming new product opportunities. But no matter what, there are some critical questions all credit union leaders should be considering in advance of the finalization of the CFPB’s open banking rule.

1. Who is going to set the data-sharing standard?

Right now, there is no one truly universally accepted standard for financial data-sharing. Yet everyone agrees that aligning the open banking ecosystem around a common set of standards—established and maintained by a standard setting organization (SSO)—will be essential to making open banking viable.

The Financial Data Exchange (FDX)—a nonprofit consortium founded in 2018 that brings together financial institutions, data aggregators, fintech providers, and other stakeholders around the creation and maintenance of “a common, interoperable and royalty-free technical standard for user-permissioned financial data sharing”—has emerged as perhaps the leading open banking SSO candidate.

In June of this year, the CFPB issued an additional rule outlining the qualifications to become a recognized industry SSO. Many observers outside the credit union industry see this as a thinly veiled message to FDX. The CFPB’s rule establishes some important parameters to encourage “balanced” decision-making at an SSO like FDX, while also holding the door open for other SSOs to emerge. The concern appears to be the potential influence certain types of organizations might have over an SSO: For example, while there are a variety of organizations participating in the FDX consortium, including third-party fintech providers, FDX has a Board of Directors and high-level membership that might be seen as weighted towards big commercial banks and data aggregators. Velera, as well as CU of Colorado, Mountain America CU, Navy Fed, and UWCU, are all “standard members” of FDX, but there are (by my count) no credit unions or credit union-focused organizations among its leadership or sustaining membership.

The credit union industry has its own open standard protocol for data sharing: Credit Union Financial Exchange. CUFX was developed by the CUNA Technology Council back in 2012. CUFX is now stewarded by Janusea, which was launched in 2022 to help community financial institutions and fintechs solve the challenge of core integration. Janusea acquired CUFX and leveraged the protocol to develop a cloud platform to facilitate interoperability between third-party fintech providers and legacy core technologies. This is—as all credit union leaders know—a persistent challenge to bringing on new partners.

Janusea is currently not a part of the FDX consortium. The company is focused not only on standards-setting, but on finding scalable solutions to the range of core integration roadblocks faced by credit unions and other financial institutions. Meanwhile, CUFX by itself remains vendor agnostic and free for credit unions to access and use. This is an interesting alternative approach to FDX, one that may be more aligned with the needs of smaller financial institutions that are more dependent on technology providers and more constrained in terms of capability and capacity.

2. Will other uses of permissioned consumer financial data be allowed?

Buried in the CFPB’s proposed rule is this important clause: “The third party will limit its collection, use, and retention of covered data to what is reasonably necessary to provide the consumer’s requested product or service.” The rule goes on to specify certain activities that are definitely not “reasonably necessary,” even when the data is de-identified: targeted advertising, cross-selling, and selling the data.

This prohibition on the secondary use of data poses challenges for third-party providers and especially for data aggregators, who may be dreaming of leveraging permissioned consumer data to do things like new product R&D. (As Alex Johnson from Fintech Takes points out, this is essentially what the credit bureaus currently do.)

It will be important to watch how this plays out in the final rule, as it has significant implications for future analytics, product development, and marketing in financial services. Would open banking spell the end of personalized offers? Or could it unlock a new era of automated personalization?

3. What will the open banking user experience look and feel like, and who’s going to manage it?

The financial services landscape is already fragmented and complex, with many consumers struggling to manage their finances across a plethora of providers with different platforms and interfaces. Open banking promises to simplify this landscape, give consumers access to best-in-class products and tools, and enable them to aggregate and disaggregate at will, selecting exactly which combination of providers they want to manage their money.

But there is also a very real possibility that open banking will simply add another layer of complexity, with consumers clicking rapidly through complex terms of service, getting confused about which provider is behind which service, and becoming frustrated by the sheer number of choices available to them and the lack of transparency about how different products or services fit together.

Under the proposed rule, consumers would interact with third-party providers, which would then connect with financial institutions. The third-party provider would get initial authorization from the consumer, and the financial institution could then directly authenticate the consumer, too. What does this process feel like from the consumer’s perspective? If onboarding doesn’t go smoothly, if something doesn’t sync appropriately, if a provider ends up doing something that—even if it’s spelled out in the terms of service—isn’t expected by the consumer, who will the consumer try to contact? Who’s going to do manage expectations, field calls to troubleshoot problems, and deal with unhappy consumers who just want their apps to work? What impact might that have on their perceptions not only of the fintech but the credit union? In short, does a more “empowered” consumer also necessitate a more informed consumer?

There’s suspicion on all sides: Third-party providers and data aggregators worry about financial institutions interfering with the consumer authorization process to limit competition; banks and credit unions worry about the experience that their customers and members will get from third-party providers and that any negative experiences will produce blowback for the banks and credit unions.

4. How will providers be vetted, and how will accountability be managed if and when things go wrong?

Security in open banking will come down to the weakest links in the ecosystem. There is thus concern that open banking, in an effort to support innovation and competition, may inadvertently open the floodgates to fraud, scams, and sketchy actors. What kind of company is asking for access to a consumer’s data? Is the consumer the person they say they are? Should financial institutions trust the KYC processes of third-party providers and data aggregators? This concern has been recognized by Director Chopra, who told one industry audience, “We want to make the barriers to entry low for the small players, but when we look across sectors where there is this openness, we don’t want the scam artists taking the biggest share.”

Then, if and when something goes wrong—a consumer is defrauded by a fake app or scammed by fraudster posing as a legitimate provider—who is liable? Where does the consumer go for redress and restitution? Who will make the consumer whole? How will consumers revoke third-party data access should they change their minds? Financial institutions may be worried that the burden of mistakes in consumer authorization will fall on their shoulders, even though that process would be managed by third parties and aggregators.

These concerns all come back to the problem of vetting providers. All the stakeholders involved—consumers, financial institutions, legitimate third-party providers, data aggregators, and the regulators—all benefit from some centralized or at least standardized way of ensuring the trustworthiness of providers. This is not a job the CFPB wants. So, what’s the end game? Every financial institution for itself? With what recourse in the case of undue risk or fraud? With hundreds of fintechs all inefficiently wading through the different vendor due diligence processes for individual financial institutions?

There is an interesting emerging conflict here for credit unions. While the CFPB seeks to encourage and incentivize openness between financial institutions and third-party providers, the NCUA has applied to Congress to expand its third-party vendor oversight authority to gain visibility into and better mitigate the risks posed by providers to systemic safety and soundness, especially with it comes to cybersecurity and data privacy. How this conflict gets worked out will be profoundly important for how open banking ends up working in practice.

5. Could open banking produce new systemic risks?

Will open banking result in a more dynamic consumer finance system, making it even easier for consumers to switch between providers and move money around? That’s the idea! Historically, banking relationships have been sticky. Open banking promises to prevent lock-in and eliminate some of the inertia or friction preventing consumers from moving from provider to provider. Is there a dark side to this dynamism? Could open banking intensify the kinds of systemic risks we saw in the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, which was hastened in part by the speed and ease with which customers pulled their money out of the bank through digital channels?

This is something both Director Chopra and Acting Comptroller of the Currency Michael Hsu have explicitly noted. Here’s Hsu: “In isolation this would likely increase the liquidity risk of retail deposits for banks.” And here’s Chopra: “There will, of course, be some real questions then about the speed of deposit flow, which will ultimately lead to thinking about the liquidity requirements that will need to be updated for insured banks.” And finally, here’s PNC Bank CEO Bill Demchak, arguing that open banking will allow his bank to “pull share out of smaller banks.”

In Europe, there’s some evidence to suggest that account switching hasn’t actually increased with open banking but has instead resulted in increased bundling of products and services by consumers. I see that as a probable outcome in the U.S., too, but credit union leaders should be asking how to prepare for a world in which bank relationships are as portable as cell phone numbers.

6. When should we expect the final rule?

I have no special insight here! But it makes sense to expect the rule to finalize before the November Presidential election—possibly around the Money 20/20 conference at the end of October.

— TN